Dança Amorosa

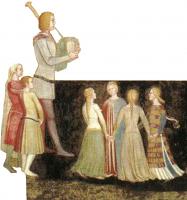

If for both sacred and secular vocal repertoire, whole volumes have been passed down to and testify to it’s wondrous blossoming, instrumental music, connected as it was to unwritten performance practice and improvisation is still confined to a seemingly limited repertoire: undoubtedly a false impression of the true significance that this repertoire held in its time. Reference need only be made to the vast amount of iconography that has reached us from Medieval times (miniatures, frescoes, sculptures, drawings depicting musicians with various instruments) to convince us of the extraordinary circulation that instrumental music, despite the little written evidence that has reached us, must have had at the time.

The few instrumental pieces that have come down to us are for the most part dances, which, and for this we must be thankful, were annotated on precious parchment. Not exactly “popular” music, but highly elaborate and refined works, worthy of being snatched, proudly and at great expense, from oblivion to stand beside the best products of the reviving culture of those centuries. An aristocratic culture, yet not for this reason in any way monolithic or monotonous, still a far cry from the strict canons of the Renaissance courts. During the first centuries of the second millennium high society would mix refined pleasures with rougher ones, the languid with the warlike, the chaste with the explicit, that fabulous with the raucous, and its dances are a faithful reflection of these trends.

A look at the context in which these dances have been passed down to us will be enough to convince us of how integrated they were in their time: we find them happily twinned with love chansons, church chants, fabulous novels, ecclesiastic chronicles, madrigals, hymns, goliardic satires, sacred and secular motets, hunts and even in the midst of a real estate registry. Some sources stand out for their wealth of illustrations; they were often compiled in a monastic context. Clearly, the eternal ecclesiastic disapproval of all mundane pleasures could little against dance as it could against music, and it just could not forbid neither its devotees nor the members of high society the enjoyment of dance music.

Modo Antiquo’s research into Medieval performance practice has enabled them to reinstate these faint echoes of past traditions into their true role as lively and gripping forms of social aggregation. Paying full homage to the abundance of instrumental colours and timbric variations that the iconographic sources as well as the literary ones pass down, Modo Antiquo has proceeded to reconstruct this repertoire that was also used as background commentary for civil and religious ceremonies or more essentially as a primary form of entertainment in those ancient forms of social life such as taverns, market places, fairs and pilgrimages. The outcome is a version that attempts to remove all antiquarian coatings off these musical tokens and to turn them into a living picture of daily life in Medieval times. These pieces have been recorded by Modo Antiquo for the Opus 111 label in Paris as part of a co-production with Westdeutsche Rundfunk and are part of the first complete edition of Medieval instrumental dances.

Modo Antiquo

BETTINA HOFFMANN

FEDERICO MARIA SARDELLI

recorder, transverse flute, double flute, shawm

UGO GALASSO

recorder, shawm, pipe and tabor, drums

MAURO MORINI

slide trumpet

PAOLO FANCIULLACCI

mute cornett, horn, bagpipe

BETTINA HOFFMANN

fiddle, rebec, trumpet marine

GIAN LUCA LASTRAIOLI

lute, citole, dulcimer

DANIELE POLI

harp, lute, dulcimer, symphonia, tambourine

PROGRAM

ANONYMOUS ITALIAN AUTHORS OF THE 13 AND 14TH CENTURIES

Ghaetta

Chominciamento di Gioia

Cançona Tedescha

Bel Fiore Dança

Trotto

Cançona Tedescha

Saltarello

Lamento di Tristano, sua Rotta

Dança amorosa, e suo Troto

Cançoneta Tedescha

Saltarello

Principio di virtu

Cançona Tedescha

Saltarello

Noci Milà

Manfredina, sua Rotta